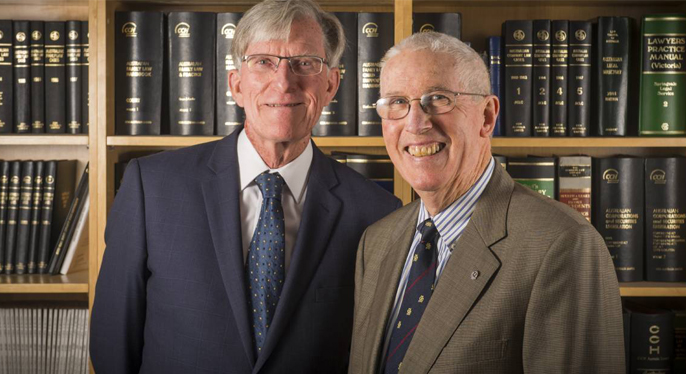

Lifelong Bendigo friends chalk up 50 years as lawyers on the same day

By Tom O’Callaghan – Bendigo Advertiser May 18, 2018

What are the chances of two lawyers clocking up 50 years of practice in the same town, on the same day?

Lifelong friends Tim Rogers and Ian Monotti recently celebrated half centuries of work in Bendigo.

As it happened, both mens’ lives and careers had in many ways developed in parallel.

“Both of us went to Bendigo High School together, both graduated from the University of Melbourne, both got degrees conferred on the same day, both got admitted to practice on the same day and both have worked for 50 years,” Mr Rogers said.

Moreover, both were twins and second generation lawyers who worked at the same firms as their fathers.

It was rare enough to clock up 50 years in practice, local lawyer Trevor Kuhle said.

“For a start, you have to still be working at least 72- or 73-years-of-age, because you would be at least 23-years-old before you were admitted into practice,” he said.

“And the fact they were in the same class at school and both returned to, and worked in, a town this size is pretty unique.”

I’ve never regretted the decision (to become a lawyer). It was something quite special to spend time practicing with my father.

Ian Monotti, second generation Bendigo lawyer

Mr Rogers’ sister has a picture of the Rogers and Monotti twins together, taken when they were two-years-of-age.

“I think my mother probably used to go around to Elsie’s (Mr Monotti’s mother) house to get advice on how to manage us twins,” Mr Rogers said.

“Elsie had a head-start. She had three boys ahead of her twins.”

After attending Bendigo High School together Mr Monotti and Mr Rogers went to Melbourne University.

They appeared on the front page of the Bendigo Advertiser in 1968. Days earlier they had qualifying to practice law as barristers and solicitors.

They were pictured along with their fathers Arthur Rogers and Merv Minotti.

In those days, it was common for sons to follow their fathers into their professions, often working in the same practice.

Mr Monotti could think of at least seven other local lawyers who followed their parents, and in some cases grandparents, into the family’s practice

“It must have been something in the water,” he said.

Mr Rogers said that in those days there was a sense of tradition that sons would, perhaps, follow in their fathers’ footsteps..

“I think my father was very subtle and made sure that I did work around the office to earn pocket money.”

Mr Monotti said his father drew a great sigh of relief when he, the youngest of five boys, finally decided to go into law.

“I’ve never regretted the decision. It was something quite special to spend time practicing with my father,” he said.

As brief as that time was – Mr Monotti’s father Merv died in 1975 – it was a cherished career highlight.

“Later on my brother came back into the practice and was very involved in a legal executive role. That was another highlight,” he said.

So too was meeting and working with his many clients, especially those in the rural and corporate sectors.

A sense of service shaped by pro bono work

Mr Rogers said one of the great highlights of his career, especially in the early years, was the sense of camaraderie between practitioners.

“I organised law association trips away,” he said.

That camaraderie was bolstered in part by a sense of supporting the community. At the time, young lawyers would provide pro bono work for the vulnerable and less well off.

“When we first came back (to Bendigo) there was no legal aid and we were expected as young practitioners to go across to the court to represent people if they could not pay fees,” Mr Rogers said.

“You would get a call from the police station. As the new boy on the block you were expected to go across and represent that person in court.”

Mr Monotti said rosters were drawn up for people to consult on an honorary basis.

“We used to take it in turns to man that (office), down by where the Bendigo Bank is now,” he said.

Young doctors would also do pro bono work at the local hospital, which created a sense of camaraderie that crossed professional boundaries.

As time went by both men would eventually eschew court work, hoping instead to manage other work they were focusing on as their busy careers developed.

The system of pro bono work that Mr Rogers and Mr Monotti cut their teeth in was not the only aspect of the legal profession that had changed during their time.

The most dramatic shift in the profession had been in technology.

Mr Monotti said when he first started, if lawyers wanted to refer to a particular statute they would go through the thoroughly up-to-date volumes stored at practices.

“You no longer need to have those because they are all recorded and available online,” he said.

Mr Monotti said the earliest example he had of technology’s capacity to accelerate the pace of legal outcomes was the introduction of the fax machine.

“We used to do a lot of work for the Sandhurst Building Society. They used to lend a lot of money in Melbourne,” Mr Monotti said.

“You would get your instructions and you would have a turnaround time of about a week, by the time they responded and provided you with the documents that you wanted.

“Then the jolly fax machine came in. They would get the letter and then, within the period of the time it took for them to read it and feed the document you wanted back into the fax machine, you had it back on your lap.”

The trick to handling technology, Mr Rogers said, was to move with the times and accommodate the changes.